One of the first things you may read about Kooikerhondjes is that they are a breed of dog so old that they are depicted in oil paintings of western Europe, especially of the Dutch Masters such as Rembrandt, Vermeer, Jan Steen, and Frans Hals. A quick Google image search will immediately show you dozens of painted scenes including Kooiker-esque dogs. But are they Kooiker ancestors? How can we tell?

Of course, we will never know for sure if today’s dogs share genes with those dogs in paintings from hundreds of years ago, but we can reasonably conclude that they fill a similar “cultural niche.” When referring to these dogs, Dutch scholars refer to them as “spioens” which is essentially an ancestral, undifferentiated spaniel-type dog. It’s worth examining what that means before diving deeper into the art history.

Spioens

“Spioen” is a Dutch word applied to early spaniel-type dogs, especially when seen in art. The word refers to a type of dog, instead of a breed, and implies a historical context, and so it does have an English translation. “Spioentje” is sometimes also used in Dutch writing, where the diminutive suffix implies a smaller dog. The spioen, or spioentje, is not a formal or well-defined breed in the way we understand dog breeds today – a written breed standard and large-scale organizations upholding breeding standards through committees and dog shows. The spioen is better understood as a “type” or “landrace” of dogs, without a formal definition as to what is or is not a spioen. English speakers can think of a spioen as an ancestral, basal, or proto-spaniel – it is not a specific breed that was called a “spioen” at the time. It is not a specific phenotype, nor does it leave a traceable genetic signature in its descendants. However, the spioen appears so often in art and historical records of western Europe beginning in the 1300s that it is assumed that the spioen is the source population for many extant breeds, and is thought of as the “proto-Kooikerhondje.” While this assumption is impossible to test scientifically, we may approach an “answer” at the confluence of art history and culture.

What “counts” as a spioen in art? This is a subjective question, but for the purposes of this article I call a dog depicted in western European art a spioen if it fulfills several characteristics. These dogs are the most commonly depicted type in paintings by Dutch Masters, and they generally share:

- A small-to-medium body size – somewhere between today’s Papillon and English Springer Spaniel. Assuming the scale of the dogs is accurate given the humans they are depicted alongside, the spioens appear to range from approximately 12 – 50 lb (5.5-22kg) and are likely somewhere between 10 and 18 inches tall (25-45cm).

- Spioens are always medium-coated with “feathers” or “furnishings.” They are never short-coated nor are they curly-coated. They are always parti-color, or predominantly white with various degrees of patchy color on their heads and in large spots across the tops and sides of their bodies. They may have patches of color of black, brown, orange, red or blond hues, or any combination thereof.

- Spioens never exhibit “extremes” in their physical characteristics. They are neither tiny nor huge. They do not tend to show remarkable characteristics like what is seen in some modern breeds such as cropped or overly long ears or short (brachycephalic) noses. Many spioens appear to have either docked or naturally shorter tails, however.

While it seems art, language and history still leaves us with a murky answer as to the origin of spaniels (both the dogs, and the words for them) depictions of spioens as early as the late 1300s in western European paintings and tapestries seem to negate the Spanish-origin theory but do not offer a plausible alternative. Regardless, we can clearly establish that the spioen “type” has been living with and hunting alongside Europeans for many hundreds of years, and the frequency with which they appear in Dutch art is likely no coincidence.

Dogs in Dutch Art

There appears to be a strong association with family – and occasionally with farmsteads – where spioens are depicted in painting. Spioens are never painted alone, and are never far from human companions. They are often in the bottom corners of paintings and are never the primary subjects, but are also not usually found in Dutch landscapes, still-lifes, or religious art – they almost always are seen in portraits or “genre” paintings – scenes of interiors or farms showing family groups. The Dutch Masters are known for their genre paintings, a type of painting for which they did not even have a specific name, showing regular people engaged in unposed activities, in regular settings – dwellings, churches, taverns, and farms.

There is a significant amount of uncertainty in interpretations of European art depicting dogs. Written records are scant and since at the time, dogs were not thought of or referred to within the context of a formal breed, texts referring to dogs do not identify types well enough to support strong conclusions. We are forced to assume that where there is a significant local tradition of genre painting depicting “regular” people in realistic situations, the dogs shown are very likely to be representative both of real individuals and of the wider population of dogs in the area. This assumption may be flawed but without direct evidence to the contrary, I operate on this assumption when evaluating the distribution and traits of spioens in Dutch art especially.

Students of art history are taught in their most basic courses that depictions of dogs in art can be symbolic. Dogs are thought to symbolize loyalty or fidelity, especially marital fidelity. The traditional interpretation of a dog depicted with a couple, woman, or man in military regalia is that the inclusion of the dog speaks to an aspect of the subject’s personality or circumstance. A military man or militia company with a dog in the foreground may be interpreted as being especially loyal in service to their homeland. Marital fidelity, especially by the woman, is most often symbolized by the inclusion of a small dog, especially when combined with notably chaste downcast glances, gestures, or dress. It is possible, then, that the spioen in the paintings of Dutch Masters are merely a “meme” or a similar-looking dog painted repeatedly and providing the same commentary on the personality of the subject. And thus it is also possible that the dogs in art history offer no reflection on living dogs and the extant breeds that resemble them now.

However, my interpretation is that the solely “meme” theory is unlikely. Similar dogs are depicted so frequently, by so many different artists across a long timespan – but the dogs retain enough individual variation between them that they are unlikely a copy of a work by a previous artist. It’s more likely that the interpretation is a combination of theories – that they do represent fidelity in varying degrees, but are also based on real dogs living near the painter’s studio.

However, consider the below painting “Prins Willem I met zijn familie en hondjes in de tuin van het Prinsenhof” by Pieter A. Haaxman – still in the collection of the Paleis Het Loo (which was a palace for the depicted family – the House of Orange – until 1984). I cannot find a digital copy of this image – this is a photo I took from the VHNK’s 1992 Anniversary Book where it was printed. I’m including only the right half of the image, but notice the dogs depicted with Willem and his family – and then consider this was painted in 1884. Centuries after the heyday of the Dutch Masters, spioens were still being included in quintessentially Dutch paintings (Haaxman painted spioens into many of his other works as well). Does this support or contradict the “spioens as memes” theory? What do you think?

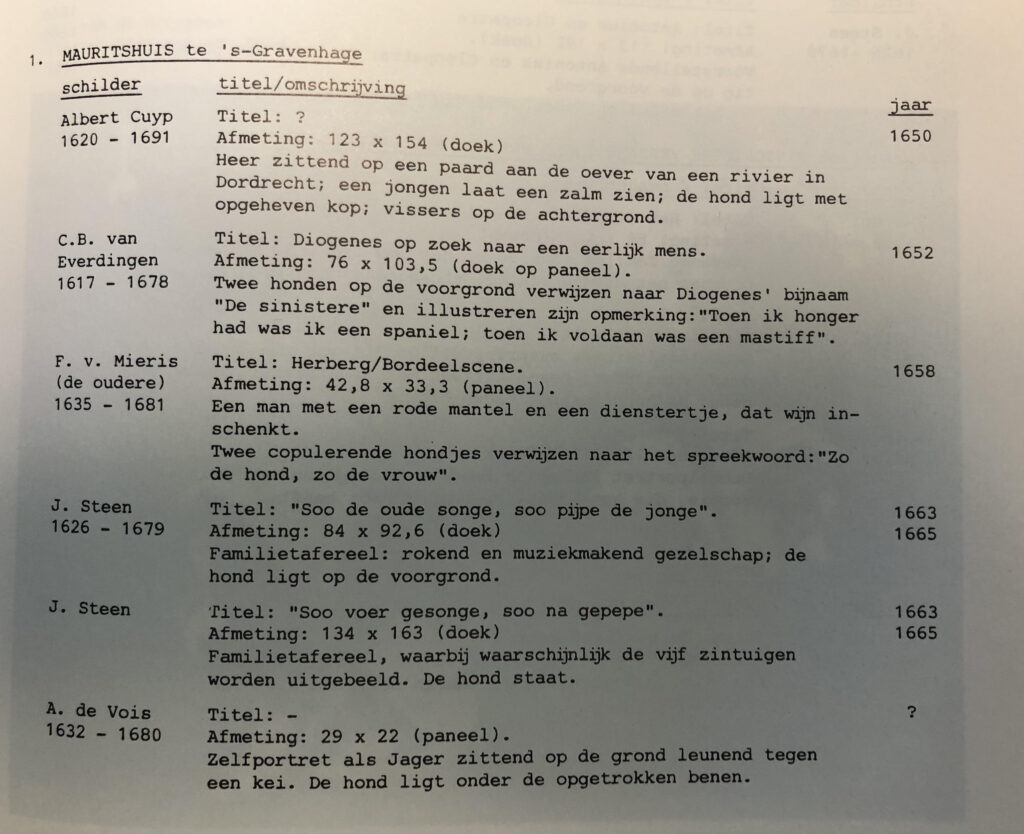

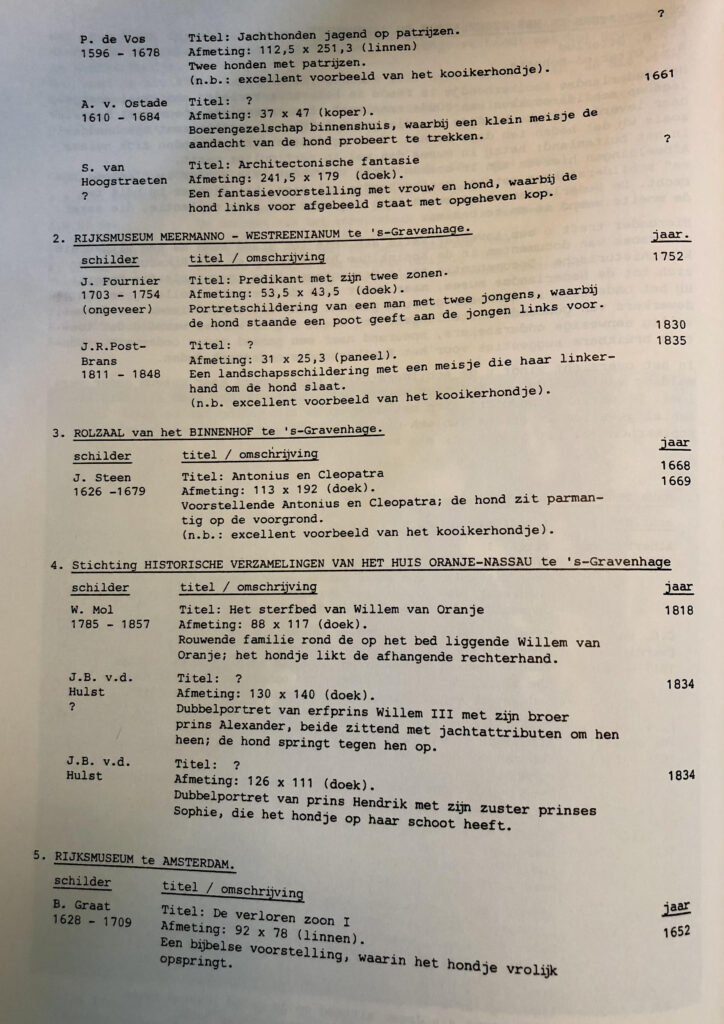

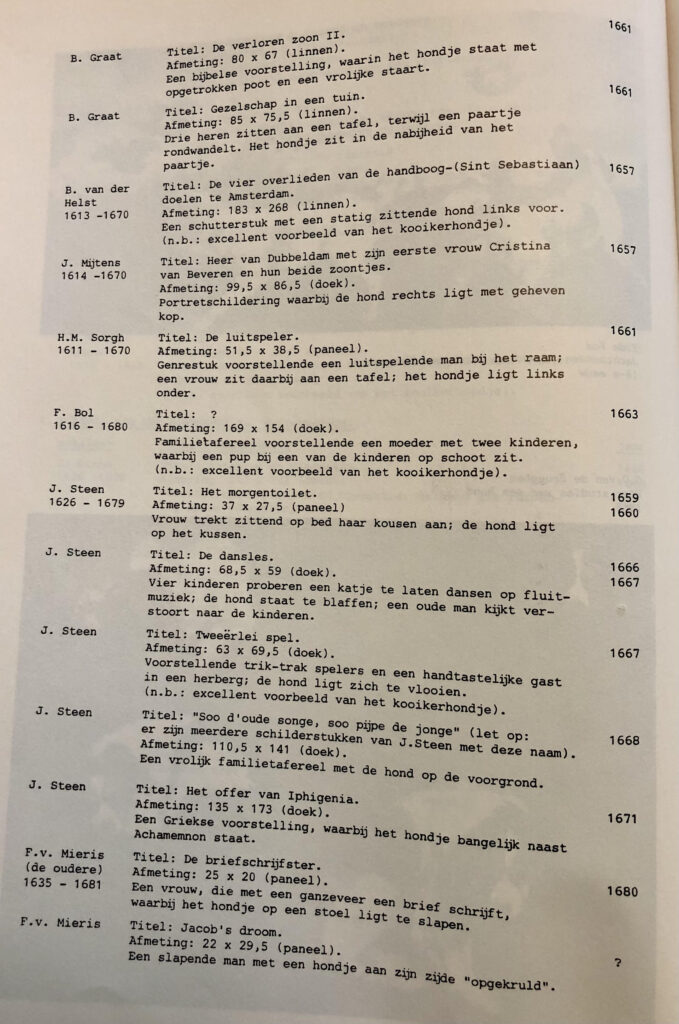

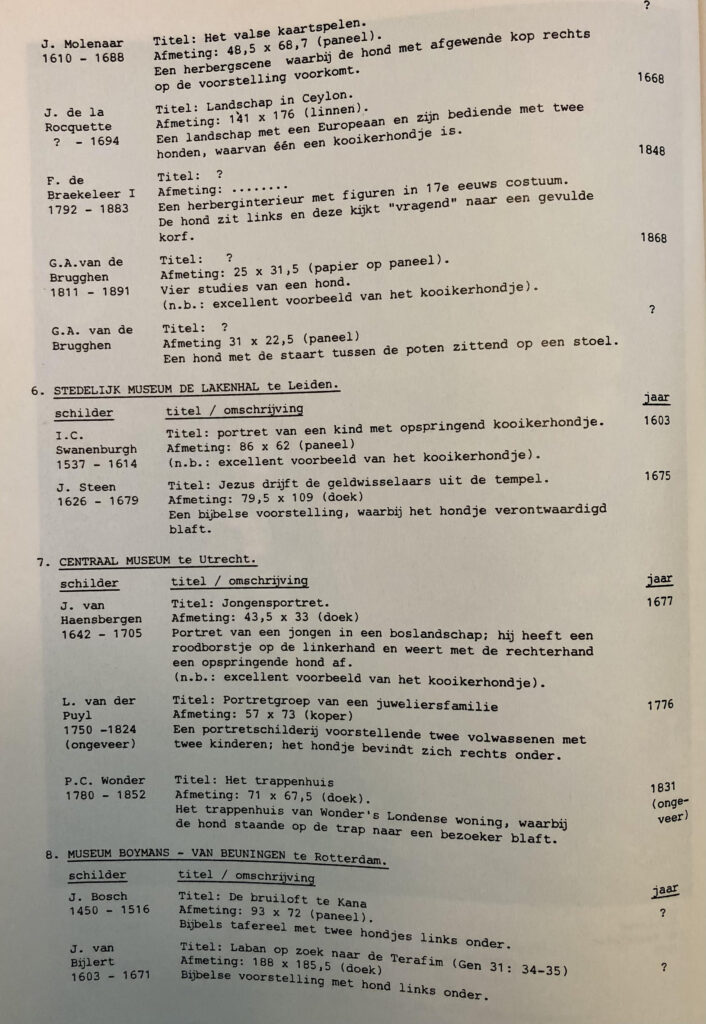

List of Dutch Masters paintings depicting spioens

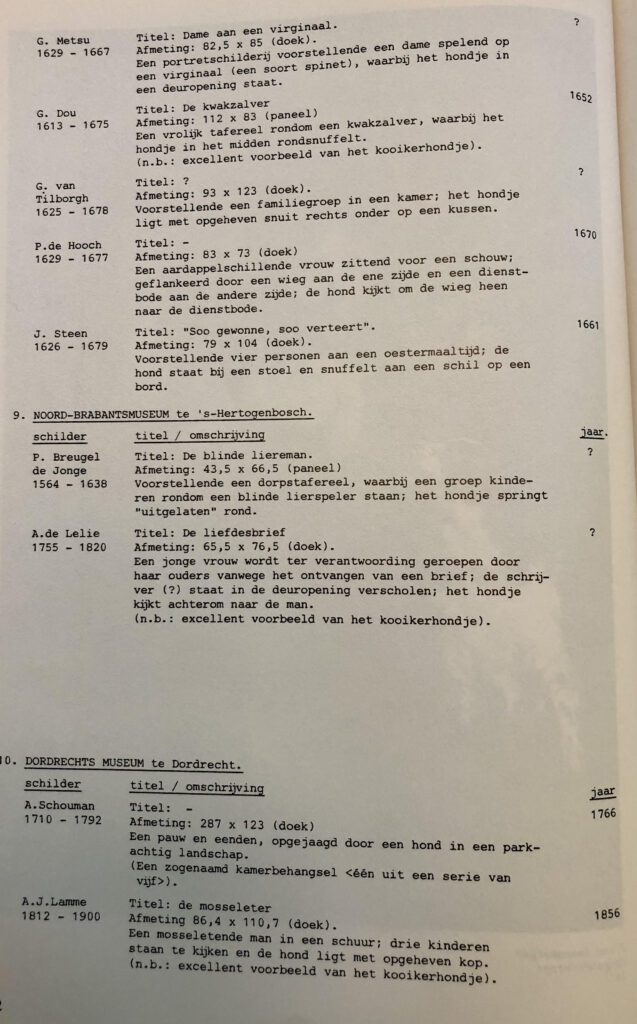

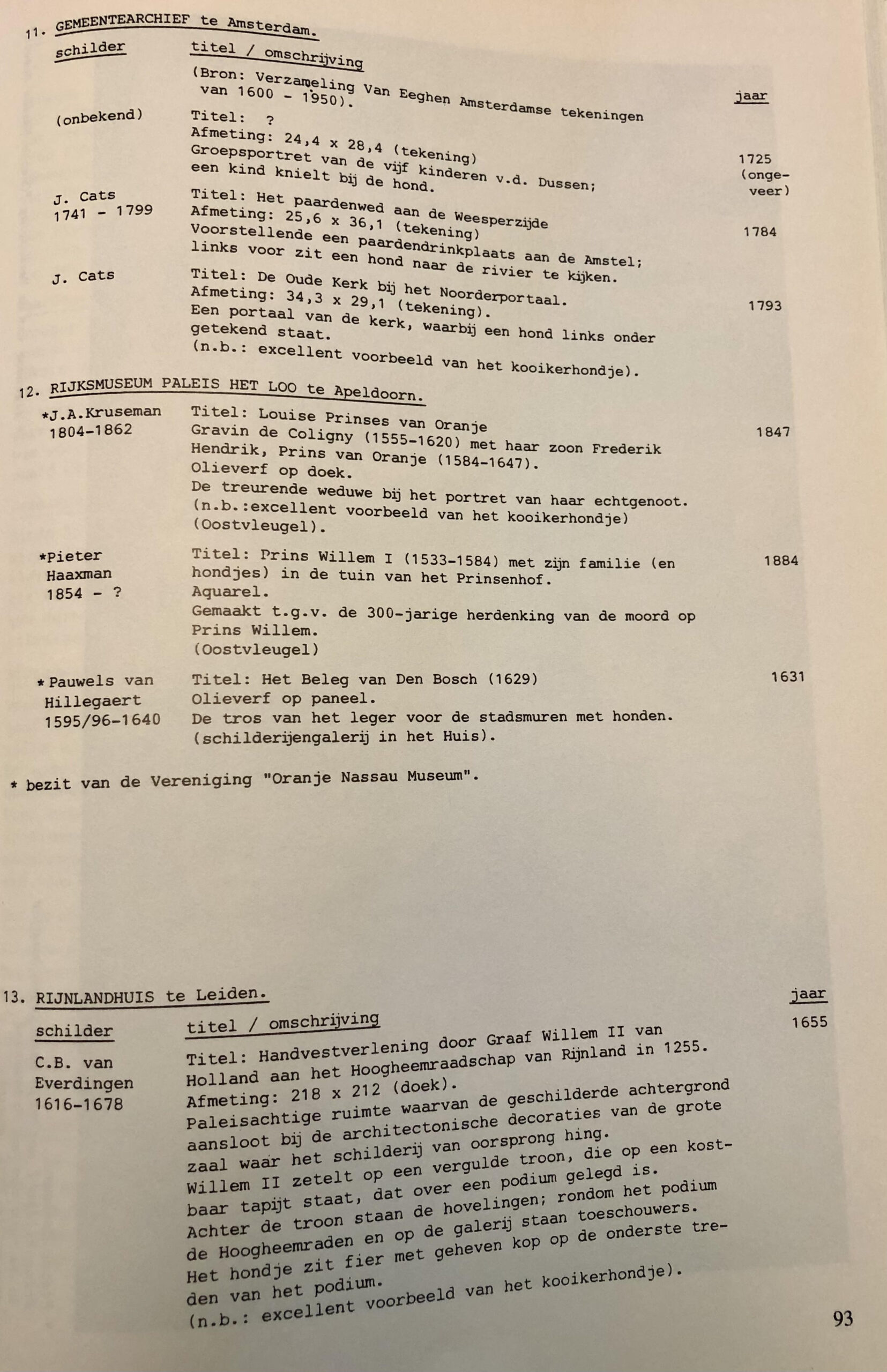

In the 1992 VHNK Anniversary Book, EGM Otterloo and AJ Otterloo-Bohneke catalogued the Dutch museums that had paintings of spioens. Rather than reinvent the wheel, here I share their list:

Recognitions

This post is an excerpt from an abandoned idea for a coffee table book on spioens in art, and the whole endeavor is very much a “standing on the shoulders of giants” situation. I primarily have to thank the historians including Mr. Laming who contributed to history articles throughout the VHNK magazines in the past, as well as the VHNK itself and editor Liliane Klever for locating these articles. Thank you also to all museum staff who have published images of these paintings and tapestries as well as articles. Biggest thanks, of course, go to the artists who included these jolly little spioens in their paintings so we may marvel at them even hundreds of years later.